By the time my Mum was off in Riverview and my sister was living somewhere else, it was mostly just Dad and me together at home. That’s one of the things I remember from when I was about 15 or 16 – just me and Dad.

As a kid, I was always looking up to him, literally and figuratively. I could remember being a kid of maybe eight or nine, walking at his right, holding his hand, and noticing that my head would barely come up to his elbow. He was like a giant to me when I was a little boy.

I was always kind of a smaller kid though. In grade eight, I remember being about four foot eleven. The phrase “ninety-eight pound weakling” grated on me, because I didn’t even weigh eighty pounds at the time.

Every year after Grade seven, I watched myself gain ten pounds and get an inch or so taller. As I gradually got older and taller into my teens, I remember always looking at Dad from the side – it was never head-on. When he was sitting in this yellow recliner, I’d be looking at his right side, across the livingroom table, on the couch. When we were driving to Safeway to get groceries, or going to the bank, I’d be sitting in the passenger seat, looking over at his right side. I guess I was his right-hand man, his loyal follower.

While sitting or standing in my father’s shadow might have given me some safety or companionship, it could also be a dark place. Any kid who’s been hit or swatted by their old man quickly learns how long his arm is, and how far away they need to be to avoid it.

Whether from the couch or from the passenger’s seat, I asked my Dad a lot of questions, mostly about my mother or my sister. I had lived under the same roof with Mum and Kim all my life, but I’d never really known what was happening to them. Only when a fight or an argument broke out would a piece of truth get revealed in our house. When pushed for answers or when he felt his privacy being challenged, Dad would always bark “Don’t air our dirty laundry in public!”

I always backed down when his temper came out. Mental illness or abuse were secret shames to be hidden, and maybe, deep down, I didn’t want to know about them. Maybe I was afraid, or just not ready.

Often when I questioned him, Dad’s answers were usually curt, vague, and never satisying. I think he hated being questioned. Maybe my inquisitiveness felt too much like an inquisition to him. Sometimes, if he got angry, he’d slam his hand down on the side of his armchair or the steering wheel. That was like the judge’s gavel coming down, telling me that he’d heard enough challenges from me. His voice, his body language, and his eyes said “I am the boss”.

As I passed my tweens and approached my teens, he still absolutely intimidated me. I wanted him to appreciate me, I wanted him to love me, and I wanted him to be proud of me.

When I was seventeen, after he had his heart attack and multiple strokes, I saw just how weak my father had become. With him lying flat on his back and me standing over his gurney or hospital bed, I was finally taller than him. I felt his dominance fading and saw weakness overtaking him, all the while my own strength and independence were starting to develop.

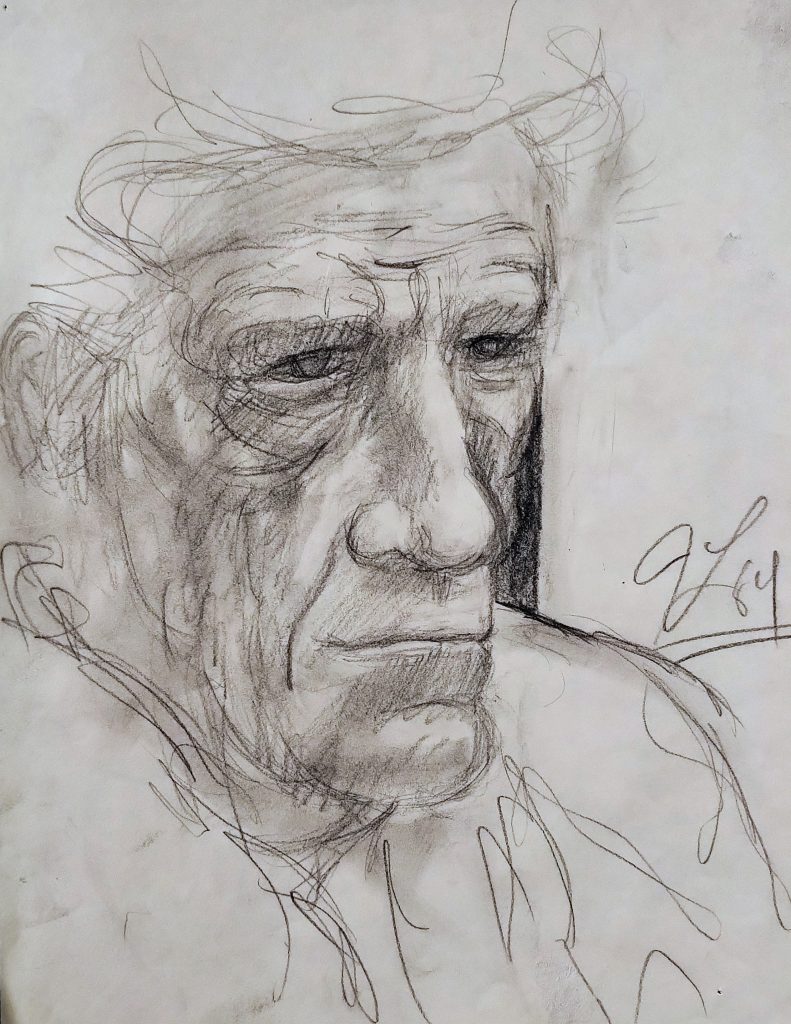

By the time he was in his care home in 1985, he was a beaten-up, toothless old tiger who would never walk again and who needed a Care Aide to help him get on and off the toilet.

I felt like an adult to him now, and he began to speak to me like one. One day, while I was visiting, he looked up at me from his wheelchair with a curious expression, and asked me “What are you now, about six feet?”

Six feet tall seemed to be the magic number for real manhood. Dad had been six foot one. At best, by the time I was nineteen, I was only five foot seven or eight. But from his lowly wheelchair, he conferred extra inches to my stature by his tone of respect.

In 1987, through a special project at my art college, I’d recently been part of an educational television series and my face had been broadcast on our provincial public TV channel. Dad bragged to the nurses that his son was an artist and was on TV. He had something to crow about again, and he was looking up to me!

I’d watched Dad face his mortality and work so hard in the stroke “activation” program at Burnaby General to rehabilitate himself back from the edge of death. I could see him much more clearly as a man with all his strengths and fears in plain sight. Stroke rehabilitation had recovered some mobility, rewired his brain a little, and finally humbled his goddamned pride. There was no more glory to be grabbed or legends to be invoked, and no more personal mystique to be trotted out and dusted off for strangers or competitors. He couldn’t even wipe his own behind without help anymore. Now, his greatest hits were just fairy tales and bedtime stories that he could console himself with. Meanwhile, he had seen me grow up and continue raising myself, to gradually become my own man.

I didn’t like everything he was or had done in his past, and it felt like as he seemed to get smaller and weaker, I felt taller and stronger. But finally, as he rolled through his last few years, I think that we really saw each other head-on, and eye-to-eye.