In second year, my drawing experiences ranged from image-making in ancient media like pencil and charcoal on paper, to modern consumer media like microcomputers. Those represented the polar extremes to me; other media like photography, audio, and video existed somewhere in-between.

Drawing with Charcoal

What did scratching out a sketch in graphite or charcoal feel like?

The act of pushing and pulling a stick of willow charcoal across paper felt like the most direct and elemental way to make a mark. I was literally dragging a little stick to scrape burnt wood across a surface.

The result of the act was immediate; nothing stood between you and the end product. Your hand and eyes were really doing the drawing, using the charcoal to make the lines and shades visible.

The stick was often brittle and irregular in shape or consistency. Little shards might snap off while you’re drawing, altering your line. You could only respond immediately, perhaps using your fingers to smudge lines into softer shapes, or redrawing lines to strengthen or improve them. It was a real-time performance, also like dancing or juggling.

It was also tactile: you could smell the charcoal and feel the material gathering on your fingers. I can still smell the sheets of cheap newsprint we drew on in class after class.

Drawing with a Computer

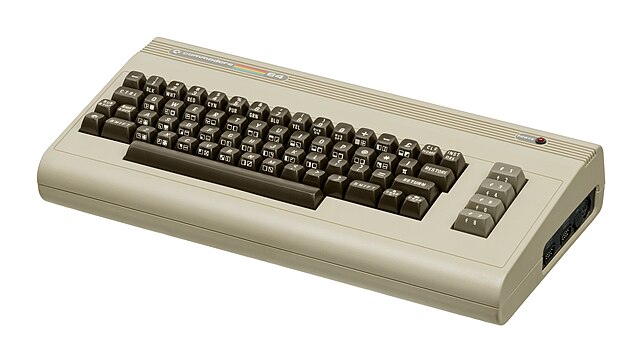

Using a computer could not have been more different. My initial experience was with a Commodore 64, typing in BASIC programming instructions to make little glowing characters appear on the monitor screen. Working on my own in the college’s computer lab, I learned how to make characters appear, how to set their colours, and how to create loops of instructions so that a few small instructions could repeat many times to easily produce a large full-screen effect.

I learned that the ability to repeat a move automatically in a loop was one of the biggest qualities of computers. The Commodore 64 (“C64”) had a screen resolution of 320 pixels wide by 200 pixels tall. By using a random number function, I could place a character of random colour in a random location on the screen. I chose to use a few similar characters that looked good together. When I ran my BASIC script, the black screen started to fill with little shapes in different places until the screen was filled. The display almost twinkled as existing characters got replaced by different ones. I wanted to see the effect in a larger way, so ran my little program on ten computers along one wall, turned out the room lights (I was the only one there), and enjoyed being the audience for a few minutes.

Pixels did feel quite magical to me. On computer monitors and TV screens, thousands of tiny LED lights built-up every image, refreshed 60 times per second. I put a slide magnifier up to TVs and video monitors to see the little regular clusters of red, green, and blue lights that made the display work. It was like a modern version of Seraut’s pointillism brought to life in light. It was additive colour theory in action. It was glowing and magical to me.

The downside of using the computer’s programming magic was that “drawing” with it was neither instant nor direct: you needed to think ahead, plan, and test a series of instructions in order to make something appear on the monitor.

Soon enough, the college bought KoalaPads, little drawing tablets with plastic styluses and a paint program that made mark-making feel a lot more like actual drawing. Finally the rudimentary C64 microcomputer could become a more natural-feeling drawing tool.

At only 320 pixels wide by 200 high, the Commodore 64 didn’t have much spatial resolution at all. By the second half of my second year, ECCAD had purchased some new Amiga computers, which had a much higher resolution display and were controlled by a mouse.

With comparatively tiny pixels as the smallest marks, and thousands of colours to choose from, the Amiga was a much better digital drawing tool, especially with a paint program like Deluxe Paint. Ironically, some of my early black and white drawings in “DPaint” almost resembled the quality of charcoal on bright, toothy paper.

On of my computer graphics instructors, Dennis Vance, described drawing with a mouse like ” drawing with a brick on a string”. He wasn’t wrong, but even so me, my classmates, and a generation of computer graphics creators became very proficient using that “brick”.